EVERYDAY ACTIONS,

EXTRAORDINARY POTENTIAL:

THE POWER OF GIVING AND VOLUNTEERING

Research and recommendations for the future of generosity

The Generosity Commission is an independent project of The Giving Institute and Giving USA Foundation™

Letter from the Co-Chairs

Long a source of stability, vibrancy, and citizen agency, civil society is American democracy’s singular asset. The organizations, associations, and networks it comprises offer forums for solving shared problems, stewarding community resources, and mobilizing bucket brigades.

At its heart are engaged individuals, “everyday” volunteers, givers, and civic leaders who are active in community life, aware of local needs, and attuned to community solutions. They join the PTA, support the local women’s shelter, or mentor 4-H youth. They put coins in the collection plate or the Salvation Army kettle. They attend town hall meetings and help clear litter from public spaces after a parade or storm. They are members of a Divine Nine sorority, belong to the Rotary Club, and help manage food drives at the Jewish Community Center. They join the volunteer fire brigade.

They vote.

Their active engagement builds trust, community, and the capacity to self-govern.

And, while their acts of generosity are selfless, their community life gives them a sense of connectedness, purpose, even joy.

Yet their numbers have fallen—precipitously.

According to the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy’s Panel Study, as many as 20 million households dropped out of giving between 2010 and 2016 in the wake of the Great Recession, when retirement savings shrank and faith in our system was tested. With rare exception, year over year more money has been given to nonprofits but by fewer givers. And year over year, more hours have been donated to nonprofits but by fewer volunteers. In short, the numbers of dollars and hours have gone up, but the number of donors has gone down.

There are several hypotheses to explain the steep fall in these forms of civic participation. Middle-class precarity is prominent among them. But whereas economics have played a large, even decisive role, social scientists note that profound social factors have also been at play, suggesting a more complicated picture. Trends in everyday giving and volunteering have occurred alongside two others: a rise in social isolation and a decline in social trust.

It was out of concern about what such trends might portend for the resilience of our society and the health of our democracy that The Giving Institute and Giving USA Foundation™—sponsors of the annual Lilly Family School of Philanthropy roundup—stood up a blue-ribbon panel of social sector leaders to better understand the forces at play.

They called it the Generosity Commission, an expression of admiration for the intention behind each person’s donation of time or treasure, no matter how large or small. The Commission’s purpose was not only to celebrate everyday givers and volunteers but to illuminate the role that they—and the organizations they support—play in our society.

To prepare for our journey, the Commission underwrote original research, took expert testimony, and conducted in-depth focus groups with everyday volunteers and givers to learn directly from them. We formed task forces of social sector practitioners and thought leaders to advise us, to solicit testimony for commissioners to hear, and to craft initial recommendations for us to consider. And we took note of the ways in which government policy, business practice, and philanthropic innovations had encouraged and enabled these expressions of generosity—and considered what more could be done.

We turned first to the question of what is at stake for nonprofit, charitable organizations when everyday volunteers and givers stay home. In a longitudinal study, the Urban Institute and colleagues found that the social sector organizations most harmed were and remain small, community-based nonprofits, many of which rely on volunteers to augment their workforce, and on local giving to meet their budgets. They are also among the organizations that build civic bridges and provide the backbone of civic life.

We then asked whether nonprofit data on which policymakers and scholars rely capture the whole of everyday giving behaviors. Research we supported under the auspices of the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society showed that while giving to and volunteering at nonprofits was in decline, generosity had found other venues and taken other forms. Long before we had a tax code and the creation of nonprofit organizations, Americans had given directly to people and causes. But the introduction of online fundraising and payment platforms expanded the practice and introduced generous individuals to an ever-wider swath of giving opportunities presented in compelling ways.

And while mutual aid is a long-standing American tradition, the pandemic lockdown gave rise to spontaneously formed mutual aid networks of volunteers helping neighbors and strangers.

Others seeking to advance the social good leverage market forces, using their purchasing power or investments to reward those companies that are contributing to the change they hope to see. “Conscious consuming,” impact investing, and online giving can be solitary activities—but the uptick of Americans joining mutual aid networks suggests a hunger for associational life.

The civic value of associational life was the focus of Commission-backed research by the Do Good Institute at the University of Maryland, which found that generous, or “pro-social,” behaviors tend to cluster. Those who volunteer and give are more likely to vote and also more likely to belong to organized groups, which are the backbone of civil society; group membership is strongly associated with participation in several other civic activities. Others have linked jury service with electoral participation. The Do Good Institute’s research brings us closer to an understanding of the connection between individual connectedness, societal resilience, and democratic functioning.

Research provides a baseline of knowledge, captured in Benjamin Soskis’ Landscape Analysis in this report. It also tees up the questions that remain unanswered but may be answerable over time. Our recommendations speak to some of the opportunities for knowledge creation, practical experimentation, policy innovation, and citizen action. They also speak to the need for public conversation because some of the most important questions can be answered only by the everyday givers and volunteers themselves, those generous actors who are reimagining giving, volunteering, and community before our eyes.

For this reason, our report, the research that underlies it, and the trends that call for it are not intended to be the last word. Far from it. Our hope is that everyday givers and volunteers will treat the report as a living document to be continuously challenged, updated, and improved over time, reflecting the dynamism of civil society and the many expressions of generosity that help define American life.

For the second stage of our work, therefore, we turned to the Aspen Institute to socialize the research, stress-test our recommendations, and invite everyday givers to offer “stretch” recommendations of their own. Aspen, in turn, has partnered with the members of The Giving Institute as well as community foundations, civic organizations, and others that convene engaged citizens locally. Together they have designed a series of community-based conversations to be carried out across the country.

Those conversations will take place in communities and on the heels of the November 2024 elections, when millions of us will have gone to the polls to cast our vote for leaders at all levels of government from the president to members of Congress, to state legislators and secretaries of state, to judges and boards of education. In some states voters will be faced with a dizzying array of ballot measures. But the work of self-governance will not end there. Regardless of who wins in each of these contests, there will be no shortage of challenges to address and decisions to make together.

To do so, we will need to make the transition from intense competition to thoughtful deliberation, from campaign to governance. We will need trusted civil society organizations and associations, and the venues they offer for argument, influence, and choice. And we will need a citizenry that is informed, engaged, and generous.

Co-Chair, The Generosity Commission

CEO, Blackbaud

Co-Chair, The Generosity Commission

Vice President, Philanthropy and Society, Aspen Institute and Executive Director of its Program on Philanthropy and Social Innovation

The story of the Generosity Commission would not be complete were we not to single out a few people who played pivotal roles.

Suzy Antounian, our director, skillfully designed and implemented the Commission’s strategy of outreach, learning, and consensus building. Kelli Gabbert worked alongside her, managing the research agenda and offering valuable insight and tactful support. We commissioned a landscape analysis by historian Benjamin Soskis, which provided a snapshot of the state of giving of time and treasure. He also served as editor of our report, capturing the consensus views of Commissioners and task force members. Jerre Stead, our quiet hero, is too self-effacing to accept the credit he deserves. But he was there whenever we needed him, connecting, introducing, and cheering us on, never suggesting the answers but rather expressing his sense of the importance of the question. Ted Grossnickle was chair of The Giving Institute when the decision was made to create the Commission. He made it his personal calling and act of volunteerism to make sure it happened, convening the initial working group and serving as the Commission’s senior adviser as it evolved from an idea to a full-fledged operation. And we were fortunate to have as full partners throughout a steering group composed of the leadership of The Giving Institute and its foundation, Giving USA Foundation™. It was a pleasure to have such deeply knowledgeable, committed, and supportive partners as Brenda Asare, Josh Birkholz, Peter Fissinger, Laura MacDonald, Erin Berggren, and the many financial supporters who came into the fold.

A full listing of all those whose contributions of time, talent, and treasure made this work possible is available in the acknowledgments section.

Executive Summary

The Generosity Commission was officially launched in 2021 in response to one of the most significant trends reshaping civil society in the United States over the last several decades: the decline, observable across multiple surveys, in the proportion of Americans who give to and volunteer with nonprofit organizations.

Co-chaired by Blackbaud president and CEO Mike Gianoni and Aspen Institute vice president Jane Wales, the Generosity Commission’s purpose is to celebrate and support everyday givers and volunteers in the United States and to recommend actions that policymakers, business leaders, foundation officers, and nonprofit innovators can take to encourage those givers’ and volunteers’ participation and help grow their numbers. The Commission embraces the term everyday not to diminish the extraordinary nature of the actions they undertake but to stress that such givers and volunteers come from all segments of American society and encompass contributions of all sizes and natures.

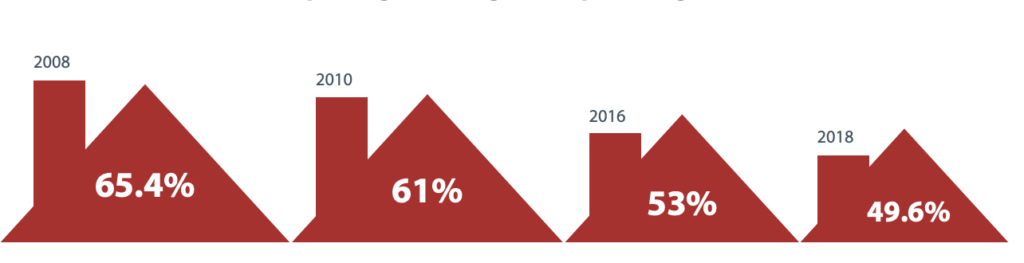

According to the Philanthropy Panel Study, the philanthropy module of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, “the only existing longitudinal dataset on philanthropy based on a nationally representative sample of U.S. households,” the share of U.S. households reporting donating to nonprofit organizations fell from 65.4% in 2008 to 53% in 2016. Then, in 2018, the latest year for which we have figures, the proportion dropped below 50% for the first time, to 49.6%.

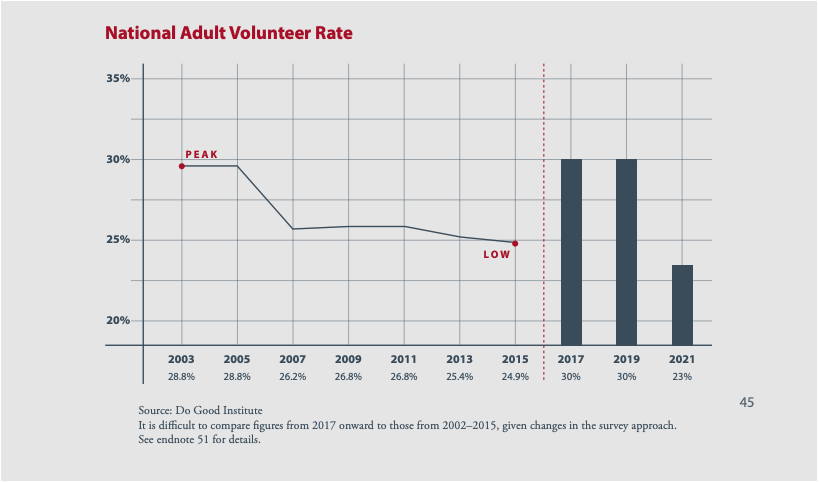

Over the last several decades, existing data suggests that the share of Americans who report volunteering with nonprofit organizations has also declined, although that decline is less precipitous. The rate of volunteerism, as measured by the Current Population Survey of the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, reached a 15-year low of 24.9% in 2015.

At first, it seemed that the COVID-19 pandemic would halt these trendlines, but by the first quarter of 2021, it had become clear that that would not be the case. In fact, according to the GivingTuesday Data Commons, there were fewer donors in 2021 than there were in 2019. Similarly, according to AmeriCorps, the federal agency for national service and volunteerism, “the formal volunteering rate dropped seven percentage points—from 30 percent in 2019 to 23 percent in 2021,” the steepest drop since the agency began collecting such data in 2002.

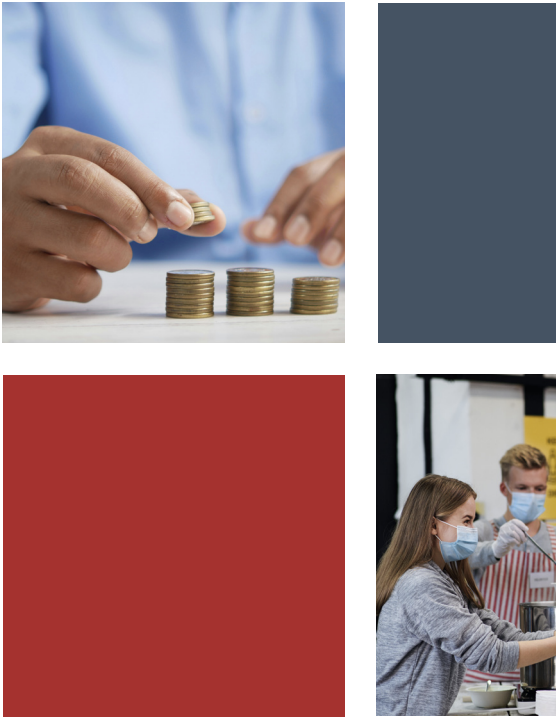

The decline in giving and volunteering rates over the last decade has sometimes been overshadowed by an increase in aggregate dollars and hours donated—termed the “dollars up, donors down” dynamic—yet it has attracted increased attention in recent years.

The Generosity Commission’s focus on that decline is tied to the belief that a broad base of participation in giving and volunteering is an intrinsic social good that should be pursued and promoted.

Why should that be the case? First, giving and volunteering are crucial means by which Americans create and participate in a pluralistic civil society, the associational space between the government and the marketplace. Additionally, giving and volunteering help solidify civic engagement more generally, affirming a commitment to work together with others toward some larger purpose. Beyond this connection to the practices of civic engagement, giving and volunteering can both reflect and foster elements of social connectedness. This is an urgently needed contribution, given what Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has recently termed the “epidemic of loneliness and isolation” that the nation faces. Increasing rates of giving and volunteering can be a means of deepening social connectedness—binding individuals together in common purpose. This is most obviously the case with volunteering, and in particular with the provision of mutual aid. But giving too can deepen social connection. In fact, in research commissioned by the Generosity Commission, Nathan Dietz of the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute determined that giving in the previous year increases a person’s likelihood of joining one or more community groups or organizations by nearly 10 percentage points; volunteering in the previous year increases the likelihood even more—by 24.4 percentage points.

On a general level, then, such arguments highlight why we should care about a decline in giving and volunteering broadly conceived. But the Commission has focused its inquiry on the decline in everyday giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations. Why does giving to and volunteering with such organizations matter? Because nonprofit organizations are, and have been for at least a century, the bedrock of American civil society, providing important services and public goods that the government and the market either have not provided or will not provide.

Of the more than 1.7 million nonprofits in the United States today, the best known and wealthiest are the large institutions, with a national or international reach—major research universities and hospitals, for instance. But the vast majority are much smaller; some 88% of nonprofits have a budget of less than $500,000. And these smaller nonprofits rely considerably more on individual contributions (as opposed to support from foundations or corporations) than do larger nonprofits. They are also more reliant on smaller donations from everyday donors than larger institutions that often have the development staff capacity to attract major donations. It is these smaller organizations, many of them operating on exceedingly thin financial margins, that would be especially hurt by a drop in charitable revenue from a decline in giving rates. Similarly, the decline in the number of volunteers has taken a significant toll on those who work for nonprofits—and thus, on the missions of those organizations.

It is possible that informal modes of giving and volunteering will fill some of these needs. But for the most part, they can complement, not fully substitute for, a robust, pluralistic nonprofit sector.

Yet even as the Generosity Commission recognizes that fact, it also recognizes that giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations represents merely one feature of a vast landscape of generosity, one whose variety has only deepened in recent decades. New modes of giving—such as online crowdfunding platforms, peerto-peer transfers through cash apps, or point-of-sale giving (at cash registers or upon payment for a service)—have proliferated. Older forms of giving, long adopted by immigrant and indigenous communities as well as by communities of color, such as mutual aid networks and giving circles, have attracted new participants. The COVID-19 pandemic cast a light on many of these practices, showing how important they were to community survival.

One of the open questions the Generosity Commission sought to address was the relationship between established patterns of giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations and the alternative modes of giving that take place outside the formal bounds of the nonprofit sector—for instance, giving to crowdfunding platforms or political campaigns. Could the decline in the former be understood with respect to the growth of the latter, in terms of a “crowding out” or displacement effect? A Landscape Analysis of charitable and volunteering trends that the Commission commissioned, and which is published as part of its final report, took this question on. It concluded not enough information exists to arrive at a definitive answer, in part because in the past, research has directed less attention to giving outside the nonprofit sector, though the report highlights a growing focus on the broader generosity ecosystem.

In fact, as part of its work studying giving and volunteering trends, it became clear to the Generosity Commission how much is still not known about how Americans give and volunteer. In its key recommendations, the Commission seeks to remedy that deficiency by recommending further efforts to track and analyze all giving behaviors, including those made outside registered charities.

Indeed, the Commission believed that in order to determine how best to address the decline in donors and volunteers, it needed to understand more about the causes that underlay those trends. As the Landscape Analysis lays out, economic precarity is clearly paramount among them, but there are others as well, including declining trust in institutions, the advent of the internet and related technological transformations, demographic shifts, changes in the workplace, and the aftereffects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Commission appreciated the major role that changes in religious affiliation and practice have played in shaping the ways Americans give and volunteer—or more recently, have chosen not to do so—and created a Faith and Giving Task Force to explore the issue. As part of its work, the Generosity Commission took expert testimony from more than three dozen scholars and practitioners and conducted listening sessions with a number of people engaged in various communities of color to learn about giving and volunteering trends in those communities. It also commissioned a number of research reports to address key issues the Commission confronted: the need to better understand the nature and causes of the shifts in generosity that have occurred in the recent past, specifically the decline in donors to and volunteers with nonprofit organizations; the necessity to support the expansion of research and data collection efforts on generosity beyond monetary giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations; and the need to learn more about the civic impacts of giving and volunteering, specifically their relationship to civic engagement and social connection. This research included work from the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society (How We Give Now: Conversations Across the United States); support for the research report Nonprofit Trends and Impacts 2021, produced by the Urban Institute and based on research conducted by a team of researchers from the Urban Institute, George Mason University, American University, and the Georgia Institute of Technology; work from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy & Practice (Generosity Trends and Impacts: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the USA); and two research reports from the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute—Understanding Generosity: A Look at What Influences Volunteering and Giving in the United States (2023) and Social Connectedness and Generosity: A Look at How Associational Life and Social Connections Influence Volunteering and Giving (and Vice Versa) (2024). With the assistance of Hattaway Communications, the Commission held a series of focus groups with everyday givers and volunteers, both current and lapsed, conducted a nationally representative survey of Americans on giving and volunteering, and conducted a media scan about the kinds of conversations about giving, volunteering, and generosity that gain traction in the media. Hattaway published insights gleaned from those sources in the report How and Why We Give: Research Insights on the Aspirations and Motivations That Inspire People to Give and Volunteer (2023). More details on this research can be found later in the final report. Guided by its task forces, the Generosity Commission began a process in which it developed nine recommendations to address the declines in giving and volunteering rates. The recommendations, which are divided into four categories (research, culture, practice, and policy), are as follows:

- Increase the depth and breadth of data on giving and volunteering

- Close the generosity evidence-to-practice gap

- Encourage public figures and leaders in a broad range of fields to speak openly about how they give and volunteer, and how they have benefited from others’ giving and volunteering

- Take youth seriously as givers and volunteers

- Utilize all of philanthropy’s resources, tangible and intangible, in support of everyday giving and volunteering

- Support community foundations to take a leading role in encouraging giving and volunteering

- Reinforce the leadership role of businesses, as conveners of employees, to encourage their volunteerism and giving

- Increase the availability of the charitable contribution tax deduction

- Sufficiently fund the IRS Exempt Organizations division and state charity regulators and simplify regulatory compliance

The recommendations the Commission offers in this report are not meant to be comprehensive, nor is the report meant to serve as the last word on the topic. Rather, the report is offered as an effort to spark a broader national conversation, as an “open” document that honors the dynamic period of cultural, social, and economic change that we now inhabit, and as the initiation of an open conversation to bring together diverse perspectives that share a common commitment to the promotion of generosity.

Why Everyday Giving And Volunteering Matter: The Mission Of The Generosity Commission

Pause and give yourself a moment. Think about the institutions, organizations, networks, and associations that you care most about, that make our communities and our world more decent, more humane, healthier, more beautiful. Soup kitchens and hospitals. Museums and after-school programs. Colleges and universities. Animal shelters and international global health charities. Houses of worship, organizations advocating for a nearly infinite range of causes, theaters, think tanks, informal neighborhood groups, and so many others. Then consider how much they rely on the generosity of those who value them. Think about the manifold ways these particular expressions of generosity take shape in our own lives. We drop coins in the church collection plate or in the Salvation Army kettle. We get involved in the local PTA or mentor struggling youth. We give blood. We lend a hand to a neighbor in need. We use Venmo and GoFundMe to support a stranger struggling with medical expenses. We participate in mutual aid networks and support groups seeking to advance societal change.

Generosity is not a term often relied upon by academic researchers, who tend to favor the more clinical “altruism” or “prosocial” behavior. In all its warm-blooded dynamism, the term resists the sort of pin-it-to-the-wall precision that can facilitate scholarly inquiry. But it’s one that this Commission has embraced. It is possible, of course, to formulate a working definition; one offered

“Generosity is more than just giving; it’s giving and doing more than is expected.”Heather Templeton Dill President, John Templeton Foundation, Generosity Commission Member

by the University of Notre Dame’s Science of Generosity Project, for instance, is “the virtue of giving good things to others freely and abundantly.” Others might be proposed as well. Yet, no matter the definition adopted, we can all appreciate that traditions of generosity offer a deep source of meaning and mutual support in our lives. They nurture the shoots of security, opportunity, and equity in every community across the United States and support a vibrant nonprofit sector that is unique in the world. At a time of growing division, generosity is one of the strongest values we share across ideologies and identities, and a consistent way we can see the best in each other.

Yet if generosity has been a constant in the life of this nation, the ways it has been expressed have always been in flux. There are moments when that change is especially pronounced, when the landscape of generosity seems to be shifting, even as familiar landmarks remain. This is one of those moments. Multiple surveys have shown that over the last 20 years, the proportion of Americans who give to and volunteer with nonprofit organizations has declined significantly. At the same time, over that period, Americans have adopted new forms of giving and volunteering, using webbased platforms and cash apps, for instance; many have also come to embrace practices with deep historical roots, such as mutual aid and giving circles.

It was in the face of those changes that The Giving Institute established the Generosity Commission, launched in 2021. Co-chaired by Mike Gianoni, the president and CEO of Blackbaud, and Jane Wales, vice president of the Aspen Institute, the Generosity Commission’s purpose is not only to celebrate and support everyday givers and volunteers in the United States but also to illuminate the role these social actors play in our society and to recommend actions that could be taken by policymakers, business leaders, foundation officers, and nonprofit innovators to encourage their participation and contribute to growing their numbers. This mission has meant holding up generosity as a value that can unite Americans while also recognizing that its expression varies widely across different communities, and that those expressions often reflect significant differences among demographic and generational cohorts. It has meant seeking ways to reverse the decline in the proportion of Americans who give to and volunteer with nonprofit organizations, while celebrating and pushing to deepen the data available on other modes of giving and volunteering directed outside such organizations, such as giving circles, crowdfunding, and mutual aid. Above all, the Commission is dedicated to promoting a response to the changing landscape of American generosity that does justice to its diversity, vitality, and import to civic life.

“The Commission’s work is not only about giving, but how we work together in America.”Ted Grossnickle Senior Consultant and Founder, Johnson Grossnickle + AssociatesChair, Generosity Commission Working Group

Marking the decline of donors and volunteers

The decline in giving and volunteering rates over the last decades, in the face of large-scale increases in aggregate dollars and hours donated, represents one of the most significant trends reshaping civil society in the United States. It reflects important social, economic, and demographic changes—from how we work and learn to how we worship, engage civically, and communicate with each other.

As outlined in greater detail in the landscape analysis of generosity that follows this introduction, the decline shows up in multiple datasets and surveys of Americans. For much of the 20th century, donating money to nonprofit organizations was an activity taken up by most Americans—as close to a widely shared norm as one gets in a country of such patchwork traditions and cultures. It became one of the most widely cited indicators of, and often a proxy for, generosity more broadly understood. But over the last two decades, and especially after the Great Recession of 2008– 2009, millions of households dropped out of the ranks of nonprofit donors and volunteers.

According to the Philanthropy Panel Study (the philanthropy module of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics), which is “the only existing longitudinal dataset on philanthropy based on a nationally representative sample of U.S. households,” the share of U.S. households reporting donating to nonprofit organizations fell from 65.4% in 2008 to 53% in 2016. Then, in 2018, the latest year for which we have figures, the proportion dropped under 50% for the first time, to 49.6%. Over the last several decades, existing data suggests that there has also been a decline in the share of Americans who report volunteering with nonprofit organizations, although it’s a less precipitous one. The September 11, 2001, terror attacks brought on a surge of volunteering, with the volunteer rate, based on data from the Current Population Survey conducted by the Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics, reaching a four-decade high of 28.8% through the years 2003 to 2005. From that peak, a modest decline was noticeable by 2006, though the volunteer rate remained steady during the Great Recession—unlike the donation rate. But after the Recession, it began to drop

“Trends in generosity and giving may appear tied to wealth but instead are reflective of a deeper sense of commitment to civil society and social connection.”Marla BlowPresident and COO Skoll Foundation, Generosity Commission Member

again, and by 2015 it had reached a 15-year low of 24.9%. And although the survey questions used to track volunteering changed in 2017, making direct comparisons challenging, existing evidence suggests that the decline has accelerated in recent years.

These are certainly concerning trendlines. But they do not tell the entire story of the state of American generosity—far from it. For giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations represent merely one feature of a vast landscape of generosity, whose variety has only deepened in recent decades. This expansion certainly applies to large-scale giving, with philanthropic foundations that once dominated the landscape now sharing space with a range of new grantmaking institutions, such as limited-liability companies, donor-advised funds, donor collaboratives, and 501(c)(4) social-welfare organizations.

Even more significant to the Commission’s purposes, the expansion applies across all wealth and income levels—for the broad category we refer to as “everyday” giving and volunteering. To call these actions “everyday” is not to diminish their extraordinary nature but to stress that they emanate from all Americans and encompass contributions of all sizes and natures. Some of these modes of giving have been around for millennia: handing money to a needy individual while passing them on the street, dropping a few coins into the church plate, or lending a hand to a neighbor or friend. Others represent more novel forms of activity. The rise and widespread dissemination of the internet and digital payment systems have allowed for the development of crowdfunding and cash apps, which can facilitate peer-to-peer giving for charitable purpose. GoFundMe, now the world’s largest charitable crowdfunding platform, reports that it has raised some $30 billion in donations to individuals and nonprofits since its founding in 2010; in 2023, 30 million people gave and received help on the platform, with the most common donation on the platform being $50. With a swipe on a smartphone, you can now Venmo or PayPal an individual thousands of miles away, whose needs have been made immediate and proximate through social media. There are more opportunities than ever to give, by rounding up a payment at the grocery store or at the end of a ride share; and there are myriad ways to support causes—by signing an online petition or practicing “conscious consumption,” for instance—that can complement formal volunteering with charitable and nonprofit organizations. While crowdsourcing platforms have not matched the online giving on platforms dedicated to nonprofit fundraising, they are rapidly growing.

“Generosity is an expression of what is best in the American spirit—the common pursuit of the nation’s well-being.”Commissioner Kenneth G. HodderGenerosity Commission Member, National Commander, The Salvation ArmyGenerosity Commission Member

“I think [generosity] is almost like a muscle. You want to keep exercising, so no matter whether it’s a small amount or a big amount, you just want to keep doing it. That way it continues as part of your life.”Cornelius35–44, GeorgiaFocus Group Participant

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence for the growth of these alternative modes of giving and volunteering, and survey data suggests they are more often favored by younger age cohorts. Yet many of these expressions of generosity do not lend themselves easily to precise measurement—or have not yet been as closely tracked as monetary giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations. That is in part because many of the main platforms that now channel such gifts lack the reporting requirements imposed on tax-exempt and tax-deductible nonprofits. So we do not yet have a clear sense of the full scale of that growth—or how it might be related to the decline in formal giving and volunteering rates. The Generosity Commission, as one of its key recommendations, encourages further efforts to track and analyze all giving behaviors, including those made outside registered charities. More independent research and data are needed to learn what percentage of giving on crowdsourcing platforms are in support of nonprofits, serve a charitable or prosocial purpose but are not intended for a nonprofit, or are in the nature of a purely private gift. Yet even with incomplete data, we can appreciate the significance of the key underlying dynamics of decline in some domains of giving and volunteering and expansion in others.

The COVID-19 pandemic perpetuated and even intensified these dynamics. It is true that there was an initial surge of giving to nonprofits in the early months of the pandemic, especially of small gifts, and an increase in donors as well, which represented a momentary reversal of the declining charitable participation rate. But by the first quarter of 2021, the trendline of decline had re-established itself. In fact, according to GivingTuesday’s Data Commons, there were fewer donors in 2021 than there were in 2019. Similarly, according to AmeriCorps, the federal agency for national service and volunteerism, “the formal volunteering rate dropped seven percentage points—from 30% in 2019 to 23% in 2021,” the steepest drop since they began collecting the data in 2002. If some of the decline represented a continuation of pre-existing trends, the pandemic certainly accelerated them, as public health considerations forced many nonprofits to suspend in-person events, services, and programming, and to turn away volunteers who had worked on site in the pre-COVID days. Virtual volunteering replaced some, but not all, of these opportunities, and many volunteers

“As is true for many other communities, the wellspring of African American resilience is a tradition of generosity—from the food provided to grieving families at a funeral repast, to the fundraising and volunteering of black fraternities and sororities, to the giving circles and donor advised funds. More research is needed to understand how these patterns of giving are being reinforced or disrupted through societal change.”Cecilia Conrad Senior Advisor, Collaborative Philanthropy and Fellows, CEO of Lever for Change, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur FoundationGenerosity Commission Member

did not return after nonprofits re-opened their doors. As the Washington Post recently reported, “Even as the need for help has increased, the number of Americans who formally volunteer has continued to decline.”

But that modifier “formally” is worth attending to. It delineates the limits of the narrative of flagging generosity during the pandemic. Outside of nonprofit organizations, a different story took shape, as many turned to informal means of helping neighbors, friends, and even strangers. The pandemic brought increased attention to modes of generosity with deep roots within indigenous and immigrant communities and communities of color, such as mutual aid networks. Some new mutual aid networks formed, and existing ones expanded, to help the housebound by offering child care, picking up groceries and medicines, providing rides to get the COVID-19 vaccine, and undertaking minor household chores and repairs when tradespeople suspended house calls. The surge of less formal modes of giving and volunteering during the pandemic fed into and was in turn fueled by a wave of activism against police violence that crested after the killing of George Floyd. Individuals contributed to (unincorporated) bail funds, sent money via cash apps to activists, contributed to and participated in mutual aid networks, marched and protested. Many of these responses would not have been registered by the most commonly cited metrics of giving and volunteering, which focus on nonprofit organizations, and so amplified questions about which actions, and which communities, get counted—and which get left out.

Why the Drop in Donors and Volunteers Matters

Those questions of “what counts” in giving and volunteering are of real civic import, and the Generosity Commission has grappled with them. Doing so has required taking full account of the broader landscape of American generosity, but that has not entailed minimizing the troubling trendlines within the nonprofit sector.

There are reasons why the decline in donors to and volunteers with nonprofit organizations over the last two decades has not, until recently, generated as much attention as the trend warrants. Its import has been obscured by the fact that, for much of the period, aggregate giving totals increased year over year, a trend sometimes referred to as “dollars up, donors down.” (Similar trends held with respect to more volunteering hours coming from a smaller pool of volunteers.)

Dollars being up is a good thing, and one that we should not take for granted, especially considering it was not the case in 2022 (in real dollars) or in 2023 (in inflation adjusted dollars). According to the authoritative tally from Giving USA 2024: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2023, total dollars given to charitable and nonprofit organizations declined by 1.1 percent from 2021 to 2022 (and 8.4 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars), and only increased by 1.9 percent (and declined by 2.1 percent in inflation-adjusted dollars) in 2023. 2022 marked just the fourth time that there has been a decline in real dollars since 1983 (while 2023 was the eleventh time that total charitable giving declined, adjusted for inflation).

But even if the decline in dollars turns out to be a momentary trend, we should still be troubled by the decline in the proportion of Americans giving and volunteering. That concern stems from one key consideration in assessments of the state of charitable giving and volunteering. There are, of course, several criteria that are often emphasized in public discourse. The most prominent involves the “how much” question, as in total aggregate dollars or hours. Another relates to directionality and purpose—what causes are being donated to or served (and which are being neglected)? There is the related issue of impact—the “so what” question of the ultimate good that is achieved by those donations or service.

A broad base of participation in giving and volunteering is itself a social good that should be pursued and promoted.

These are all worthy considerations, although they are not the Commission’s focus. Instead, it has trained its attention on a set of different but related questions: who gives and who volunteers, and, more precisely, how many give and how many volunteer? That focus is staked to the belief that a broad base of participation in giving and volunteering is itself a social good that should be pursued and promoted.

Why is this the case? First, giving and volunteering are crucial means by which Americans create and participate in a pluralistic civil society, the associational space between the government and the marketplace. As much as voting or protesting, giving and volunteering are expressive acts of civic significance, ensuring that individuals’ views about what matters are reflected in the world. The more individuals who give and volunteer and the wider and more diverse the base of giving and volunteering, the greater and deeper will be that pluralism, so that American civil society will reflect a broad range of organizations, viewpoints, interests, and perspectives. Our communities are stronger, our cities, states, and country are stronger, when individuals harness their divergent interests, commitments, and beliefs, in all their particularity, toward their understanding of the public good. Giving and volunteering are vital instruments in doing so.

Another reason to encourage a broad base of giving and volunteering is that those actions also help to solidify civic engagement more generally. Some giving, of course, is purely transactional, completed with a click and a moment’s thought. But going back as far as the French nobleman Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations in the 1830s, there has long been a belief that voluntary associations can serve as schools of democracy in which we learn how to work together toward a common mission and purpose (although there are also forms of associational activity that can be threats to democratic norms and institutions). Giving to and certainly volunteering with an organization can be important steps in participating in its workings. They can also affirm the commitment to civic responsibility more generally, to working together toward some larger purpose. Indeed, in research commissioned by the Generosity Commission, Nathan Dietz of the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute has found that volunteering and giving in the recent past appear to increase the likelihood that adults will vote in national elections.

“I want to show I care. And I care about not only the people that live here now, but the people who are going to live in the community in the future.”Bakari31–35, MarylandFocus Group Participant

Even more than this connection to the practices of civic engagement, giving and volunteering can both reflect and foster elements of social connectedness. This is an urgently needed contribution. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has recently warned that we are in the midst of an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation” constituting a public health crisis of social disconnection. Murthy has cautioned that the “mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.” This increase in social disconnection may be in part responsible for declines in formal charitable and volunteering participation.

“The U.S. government provides such a scant social safety net that there would be even more economic disparity without nonprofits of all structures lovingly and creatively filling in the gaps.”Valerie RockefellerGenerosity Commission Member, Chair, Rockefeller Philanthropy AdvisorssGenerosity Commission Member

When the donor pool shrinks, smaller, local organizations—those meeting the needs of communities across the country—lose out most of all.

Relatedly, there is extensive evidence that giving and volunteering is good for you—with respect to both physical and mental health. Studies have shown that giving and volunteering are associated with living longer, greater subjective well-being and happiness, healthier relationships, and fewer psychological problems. And this is not just a phenomenon that has been documented in the United States or in Western nations—the relationship between generosity and positive physical and mental health seems to be a universal one. It is true that there is also evidence that mentally and physically healthier people are more likely to give and to volunteer, but much of the research does point to a causal relationship linking generosity to health—including identifying the potential underlying biological mechanisms.

None of this should be surprising. As humans, we have a fundamental need to give and to receive, to serve and be in solidarity with others.

The Importance of Giving to and Volunteering with Nonprofit Organizations

At such a level of generality, these arguments highlight why we should care about a decline in giving and volunteering broadly conceived. But the Commission has focused its inquiry on the decline in everyday giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations. It believes this more specific dynamic demands increased attention—and should cause some alarm. After all, it is possible to celebrate an expansive understanding of giving and volunteering in all their forms while also recognizing that the decline of donors to and volunteers with nonprofits has had, and will continue to have, dire consequences.

Why does giving to and volunteering with nonprofits matter? Because nonprofit organizations are, and have been for at least a century, the bedrock of American civil society, providing important services and public goods that the government and the market have not provided or will not provide. There are more than 1.7 million nonprofits in the United States today. The best known and wealthiest are large institutions, with a national or international reach— major research universities and hospitals, for instance. But the vast majority are much smaller; some 88% of nonprofits have a budget of less than $500,000. And these smaller nonprofits rely considerably more on individual contributions (as opposed to support from foundations or corporations) than do larger nonprofits. They are also more reliant on smaller donations from everyday donors than larger institutions that often have the development staff capacity to attract major donations. Given that most nonprofits are working with exceedingly thin financial margins—according to the Nonprofit Finance Fund’s 2022 State of the Sector Survey, 45% of nonprofits don’t have any operating reserves—any drop in charitable revenue could force organizations to make cuts to programs or staffs. That likely would mean that some who are hungry will not be fed, plays will not be performed, students will not be tutored, research will not be produced, causes will not be championed, and all sorts of other work that might have been accomplished, given greater resources, will go undone.

A wide donor base is important for a healthy, pluralistic nonprofit sector. But the “dollars up, donors down” trend represents an arrangement in which, even if more financial resources are available for nonprofits in the aggregate, an increasingly smaller cohort of donors and volunteers have their views represented through the organizations and associations that they favor with their dollars (or their service). Recent research has shown that the decline in donors is concentrated among Americans at the lowest income levels or wealth strata. We also know that the giving preferences of high-net-worth donors skew more toward higher education and medical research and less toward religion than those of small-dollar donors, and that they tend to favor the largest, wealthiest institutions. When the donor pool shrinks, smaller, local organizations—those meeting the needs of communities across the country—lose out most of all.

Similarly, the decline in volunteers has taken a significant toll on those who work for nonprofits, and thus on the missions of those organizations. Soup kitchens now must make do with fewer volunteers to help in the kitchen, for instance, even as they face rising food costs and increased demand. “Not having enough people in the kitchen to prepare everything and get it ready for our guests puts a lot of strain on the chefs and the other volunteers,” a volunteer chef who works at a local charity recently told The Washington Post.

It is possible that informal modes of giving and volunteering will fill some of these needs. But for the most part, they can at best complement—not fully substitute for—a robust, pluralistic nonprofit sector. If there was any doubt, nonprofits proved their worth during the pandemic, providing a vital lifeline for countless Americans, even as informal networks of generosity sprouted up as well. Nonprofits can more easily achieve the organizational continuity and longevity that is essential for community resilience. The nonprofit sector also operates under a system of regulations governing transparency and accountability. It is by no means perfect, but when giving and volunteering are done outside the nonprofit sector, they are also done outside that system. Sometimes that is precisely the point: some find special value in giving and volunteering that are free of any entanglement with government bureaucracy. But giving and volunteering directed through channels that circumvent the nonprofit sector carry a risk that the activities are not subjected to formalized public oversight.

By encouraging a broad base of giving and volunteering, the Commission hopes to ensure that an equally broad base of nonprofit organizations will have the resources they need to do their vital work.

The Commission’s Research and Learning

One of the first steps the Generosity Commission took to meet that objective, even before its formal launch, was to support the initiation of several research projects. The Commission believed that determining how best to address the decline in donors and volunteers required understanding more about the causes that underlay those trends. Economic precarity was clearly paramount among them, but there are others as well, including the declining trust in institutions, the advent of the internet and related technological transformations, demographic shifts, changes in the workplace, and the aftereffects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Commission was also interested to learn more about whether certain forms of giving, especially giving outside the formal bounds of the nonprofit sector (to crowdfunding sites or political candidates, for instance), might be displacing or “crowding out” giving to nonprofits (for more on this question, see the landscape analysis that follows).

The Commission appreciated the major role that changes in religious affiliation and practice have played in shaping the ways Americans give and volunteer—or more recently, have chosen not to do so. Out of that focus, it created a Faith and Giving Task Force—among the four it established to assist in its work (the others dealt with Communications, Research, and Policy). In the recommendations made to the Commission, the Faith and Giving Task Force wrote, “while researchers have long recognized the important role that faith plays as a key predictor of giving behaviors, far too often faith is overlooked in our focused attention on charitable giving.” The Commission made sure this was not the case in its own work; a focus on faith, and the myriad ways it is expressed, was a defining feature of the Commission’s approach to its mission.

As part of its work, the Generosity Commission took expert testimony from more than three dozen scholars and practitioners. The Commission learned an enormous amount from those individuals. It also listened to a number of individuals engaged in various communities of color to learn about giving and volunteering trends in these communities. But when surveying the broader landscape of American generosity, the Commission also quickly recognized how much still was unknown. Most significantly, there is a lack of data on giving and volunteering unmediated by nonprofits. Efforts have now begun to remedy this deficiency; GivingTuesday, for instance, has recently constructed a Data Commons, involving a remarkable coalition of data aggregators, commercial payment platforms, and philanthropic and nonprofit leaders working to capture data on gifts made for charitable purposes but not to or through registered charities. This is an important collaborative undertaking, and among the Commission’s recommendations is that this effort and similar ones be joined, supported, and accelerated.

Ultimately, the research that the Commission supported sought to advance a few key objectives:

- Better understand the nature and causes of the shifts in generosity that have occurred in the recent past (with a particular emphasis on the COVID-19 pandemic), specifically the decline in donors to and volunteers with nonprofit organizations, and identify ways of potentially reversing that decline.

- Support the expansion of research and data collection efforts on generosity beyond monetary giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations, and support research on giving and volunteering practices that reflects the full diversity of the American public.

- Learn more about the civic impacts of giving and volunteering, specifically their relationship to civic engagement and social connection.

With those goals in mind, the Commission funded the following research studies, which are outlined in fuller detail later in this report:

How We Give Now: Conversations Across the United States (2020). Conducted by a team of researchers at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and led by philanthropy scholar Lucy Bernholz, this research sought to improve our understanding of the different ways that people give their time, money, and other resources, reinforcing the breadth and scope of generosity in the U.S. across a broad range of communities. Informed by 33 facilitated group discussions held in 15 states and the District of Columbia, the research illuminated the generosity behaviors that reach far beyond the kinds of activities that are officially counted or incentivized in the U.S.—most notably tax-exempt donations to charitable organizations—and provided the foundation for Bernholz’s 2021 book, How We Give Now: A Philanthropic Guide for the Rest of Us.

Nonprofit Trends and Impact Study (2021). This study, produced by the Urban Institute and based on research conducted by a team from the Urban Institute, George Mason University, American University, and the Georgia Institute of Technology, examined trends in donations to community-based and social service organizations across the U.S. and provided an understanding of the impact of the pandemic on these institutions. The study revealed that in 2020, donations fell for 42% of small organizations and for 29% of large organizations across all types of nonprofits. It represents findings from the first-year survey of the Nonprofit Data Panel Project, the first nationally representative, ongoing panel study of nonprofits, which will analyze long-term effects of trends in the nonprofit sector through annual surveys.

Generosity Trends and Impacts: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the USA (2022). This study, from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy & Practice, tracks the generous behaviors of U.S. adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, including formal giving and volunteering through nonprofit charitable organizations, informal giving and volunteering that are not mediated by those organizations, such as helping a neighbor or giving money for a special need, and other pro-social behavior, such as donating blood or engaging in political advocacy. Among other findings, the report showed that the total number of donors fell during the pandemic, but that the average donation amount rose by over 200%, and that informal giving and volunteering rates remained stable during that period.

Understanding Generosity: A Look at What Influences Volunteering and Giving in the United States (2023). The first of two research reports from the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute, it explores the decline in the volunteer and giving rates through the lens of micro-level influences (individual, family, and household characteristics) and macro-level influences (state- and metropolitan-level characteristics). A second report, Social Connectedness and Generosity: A Look at How Associational Life and Social Connections Influence Volunteering and Giving (and Vice Versa) (2024), adds meso-level variables (influences of groups, organizations, and social networks) to the analysis to examine the social determinants of generosity, and explores the relationship between different types of civic behavior. Most notably, this report found that group membership significantly influenced giving and volunteering behavior, and giving and volunteering increase the likelihood of voting in national elections.

While the Commission learned much through research and testimony, it gained special insights from listening to everyday givers and volunteers and those they serve and support. With the assistance of Hattaway Communications, the Commission conducted a series of focus groups with everyday givers and volunteers, both current and lapsed; a nationally representative survey of Americans on giving and volunteering; and a media scan about the kinds of conversations on giving, volunteering, and generosity that gain traction in the media. Hattaway published insights gleaned from these sources in a report, How and Why We Give: Research Insights on the Aspirations and Motivations That Inspire People to Give and Volunteer (2023).

The survey results suggest that most people identify as generous and do not believe there is a right or a wrong way for people to practice generosity. They also expressed that generosity could be exhibited by everyone and could be shown to everyone, not only those who are traditionally considered to be in need. While everyday givers describe generosity as boundless, they perceive giving and volunteering to be resource dependent. In other words, while those interviewed celebrated that anyone can choose to be generous at any time, they appreciated that people might make financial contributions or volunteer only when they have the resources to do so. These sentiments were echoed in the focus groups the Commission conducted: People wanted to give and thought it should be a priority, but they felt hindered by time, money, and a general feeling of helplessness. They also expressed a desire for control over when and how to fit volunteering into their lives, and frustration that this often isn’t possible with the volunteer opportunities they find. They felt strongly that their own generosity matters and emphasized the importance of ensuring that everyday giving and volunteering isn’t overshadowed by reports of large-scale philanthropic donations or spectacular acts of service.

Recommendations

Guided by its task forces, the Generosity Commission then began a process in which it developed nine recommendations to address the declines in giving and volunteering rates; the recommendations can be found later in this report.

The recommendations were divided into four categories: research, culture, practice, and policy. As a whole they are directed to a broad audience, but several are aimed in specific directions: at leaders of nonprofits, at funders, at researchers, at policymakers, and at business leaders. The recommendations are outlined briefly below.

Research

Generosity Commission calls for more timely, comprehensive data on all forms of giving and volunteering in the United States, to gain a fuller understanding of the broad ecosystem of generosity. This means a particular

focus on data and analysis on giving and volunteering beyond that done to and through nonprofit organizations. The Commission also calls for additional research about the connections between faith and giving, for continued

support for experimental research on giving and volunteering, and for improvements in the quality and access of public data related to giving and volunteering.

The Commission urges funders to support this research as well as research on effective fundraising practices, and urges researchers and nonprofits to work together to make sure it is widely disseminated and targeted to the needs of practitioners, in order to close the “Generosity Evidence-to-Practice” gap.

Culture

The Commission stresses the need to make sure that generosity, particularly giving and volunteering, has a visible place within popular culture and public discourse commensurate to its importance to our nation’s civic health.

This requires producing and promoting more narratives that uphold the contributions of nonprofits in the lives of Americans, to increase the public’s familiarity with and trust in them. It also requires encouraging more

public figures in a broad range of fields—including arts, religion, and sports—to speak openly about how they give and volunteer, and how they have benefited from others’ giving and volunteering. The Generosity Commission

also calls for a greater focus on youth in narratives and public conversations about generosity, giving, and volunteering.

“Generosity makes [the world] feel safer. It shows you people you can depend on.”Rachel36-40, FloridaFocus Group Participant

Practice

The Generosity Commission offers specific recommendations for fundraisers, philanthropic funders, and nonprofit and business leaders, to promote a wider base of giving and volunteering. The Commission calls for greater

philanthropic investment in fundraising capacity, so that fundraising can be conducted across as broad and diverse a range of communities as possible. This means investing in the fundraising capacity of smaller organizations,

in organizations that serve communities of color and that are led by people of color, and in the potential of everyday donors and volunteers. Funders should invest in support staff for volunteers as well, and should

consider funding outside the formal nonprofit sector, to further bolster the enabling environment for generosity (although it is especially important to do so with respect for the autonomy of the recipient organization).

Beyond monetary contributions, funders can also utilize their networks and public voices to support expanding the base of donors and volunteers.

The Commission has highlighted an important role for community foundations in promoting giving and volunteering, and for employers, who can help bolster the workplace as a locus and incubator for generosity. The Commission believes that businesses of all sizes, not just larger firms with more resources for subsidizing employee generosity, should embrace this role. The Generosity Commission identifies several ways that employers can strengthen workplace volunteering opportunities, as with a volunteer grant program that would provide grants for a certain number of hours volunteered by employees to their favorite organizations, and workplace giving opportunities, as with matching gift programs that enable employees to match gifts to their preferred organizations.

Policy

The Generosity Commission has not endorsed specific legislation, but it does encourage policies at the local, state, and federal levels that will promote greater participation in giving and volunteering. More generally,

the Commission seeks to elevate increasing the number of donors and volunteers as a key priority in policymaking. The Commission highlights several ways to do so, such as by adopting legislation that increases the number

of taxpayers who can receive tax benefits from charitable contributions, as with a universal “above the line” charitable tax deduction.

The Commission also encourages adopting public policies that would increase trust in the nonprofit sector, which has been shown to be a key factor in leading individuals to give. Since one important component of bolstered trust in nonprofits is securing effective regulation and enforcement, the Commission urges Congress and the states to fully fund the IRS Exempt Organizations division and state charity offices. Doing so will allow staff to adequately support the nonprofit sector, the funding for nonpartisan investigations, and the technological innovations that can simplify compliance and enforcement.

Sparking a National Conversation

The recommendations that the Commission offers in this report are not meant to be comprehensive, nor is the report meant to serve as the last word on the topic. Rather it is offered as an effort to spark a broader national conversation, an open document that honors the dynamic period of cultural, social, and economic change that we now inhabit.

The Commission hopes this conversation can fill the space between reticence—as many individuals are still uncomfortable talking about giving and volunteering—and gauzy abstraction—with others satisfied to talk about generosity as a timeless, tireless virtue but not grappling with how its expression might be changing in today’s world, and why those changes matter. One way we can show that we do not take generosity for granted is by elevating it as a topic in public discourse and civic life.

Ultimately, then, the Commission’s hope is that our report becomes a living document, revised and updated by everyday givers and volunteers in their own voices, based on their own experiences and reflecting their own motivations and aspirations. These voices can help us all understand more about the ways in which giving and volunteering practices are changing, which changes we want to encourage and lean into, and which we seek to counter, in order to inspire greater participation by Americans of all ages, genders, races, cultures, religions, and means. Indeed, such an open conversation, bringing together diverse perspectives that share a common commitment to the promotion of generosity, can itself serve as an inspiration. It can do justice to the best in us, that which is the wellspring of generosity.

The Shifting Landscape Of American Generosity

Benjamin Soskis, Urban Institute

Over the last century, surveys of the landscape of American generosity have been dominated by a single feature: the longstanding year-over-year increase in the aggregate dollars Americans have given to tax-deductible nonprofit organizations. “For as long as records have been kept,” noted sociologist Robert Putnam in 2000, “total giving in current dollars has risen steadily.”1 Nearly a quarter century later, the statement still largely holds. According to the latest accounting from Giving USA (as of this writing), Americans gave $557 billion to charity in 2023, more than a third more in inflation-adjusted dollars than when Putnam made his pronouncement.2

There has long been something reassuring about the steady, seemingly inevitable ascent of that slope. Directing one’s attention toward the statistical summit could confirm notions of American charitable exceptionalism.

In 2022, though, the view from the top began to look different, with the total amount raised representing a decline of 8.4% from the year before in inflation-adjusted dollars; in 2023, total giving fell by another 2.1%. Yet even before 2022 was pegged as “one of the worst years in philanthropy history,” in the words of The Chronicle of Philanthropy, it was already clear that

Another feature has come to rival the upward slope of total dollars donated to nonprofits: the gradual downward slope of the proportion of Americans who donate to or volunteer with them.

the landscape of American generosity was in fact more varied, and perhaps less welcoming, than a vista of steadily rising annual totals would suggest.3 For one, the upward slope of charitable giving is craggier than it might seem at first inspection, featuring multiple local peaks and valleys. When giving amounts are adjusted for inflation, for instance, total charitable giving has actually declined eleven times since 1983.4 And even commentators who have marveled at the long-term growth in charitable giving have also acknowledged the apparent limits of the phenomenon. Total charitable giving as a percentage of U.S. GDP, and individual giving as a share of disposable personal income, have hovered around 2% for nearly half a century, never veering more than 0.3 percentage points higher or lower. In at least this respect, though Americans might have given more dollars one year than the years before, we are not becoming more generous.5

In fact, at higher resolution, such statistics can indicate not growth but decline. In his 2000 book, for instance, Putnam announced that “trends in American philanthropy relative to our resources are dismaying.” He noted that in the late 1990s Americans donated a smaller share of personal income to charity than they had at any time since the 1940s and that the proportion had been steadily falling since the 1960s. Similar observations have been made more recently. In 2022, individual giving was 1.7% of personal disposable income—matching its lowest point in the last four decades.6

In other words, even as recent assessments of American generosity have been dominated by the sense of assurance produced by the top-line, aggregate giving totals, they have also contained undercurrents of apprehension. In this light, the disappointing giving totals for 2022 (and, to a lesser extent, 2023) register less as a shock and more as a confirmation of persistent nagging anxieties. In fact, in recent surveys, another feature has come to rival the upward slope of total dollars donated to nonprofits: the gradual downward slope of the proportion of Americans who donate to or volunteer with them. This is not necessarily a new concern. Surveys in the 1980s and 1990s noted a decline in the proportion of American adults who reported making a contribution to charity in the last month; even before then, the influential Filer Commission (the Commission on Private Philanthropy and Public Needs), which conducted its research in the 1970s, was motivated by an aim to “broaden the base of philanthropy” and concerns that the base was shrinking.7

More recent household surveys, including one which offers a longitudinal perspective, have provided an even more rigorous analysis of American giving habits and have confirmed this decline.

Taken alongside the increase in aggregate amounts donated (or total hours volunteered), this is sometimes referred to as the “dollars up, donors down” phenomenon. Nathan Dietz and Robert T. Grimm, Jr. of the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute describe it this way: “While the United States recently experienced record highs in total volunteer hours and charitable dollars given to community organizations, these seemingly positive numbers mask a troubling trend: fewer Americans are engaging in their community by volunteering and giving than in any time in the last two decades.”8

So, the landscape of American generosity is marked as much by decline as it is by increase. In recent years, surveyors of that landscape have begun to give as much attention to the former as to the latter. That perspective has dramatically reshaped contemporary assessments of the state of American generosity. Yet so too has another development: the increased willingness to expand the scope of the survey beyond monetary contributions to nonprofit organizations and direct more attention to informal modes of generosity, to giving to entities not registered with government agencies, and to all the many ways that people, either as individuals or as collectives, care for one another, their communities, and the causes they hold dear. The territory had always been there, but analysis of American giving and volunteering had rarely attended to what GivingTuesday has called “the whole generosity ecosystem.” 9

Analysts’ newfound willingness to do so raises two questions that are central to this analysis— though neither is definitively answered by it. The first relates to the extent to which this shift in attention toward a broader generosity ecosystem reflects actual shifts in the practice of generosity. The second question touches on the relationship between the two coincident trends: declining participation in formal charitable giving and volunteering and shifts within the broader generosity ecosystem.

With respect to that second question, a number of possibilities have been offered, although they remain only that; as the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy explained in a 2021 report, “researchers do not yet have a full understanding of how the two trends are related.”10 The strongest causal link asserted between declining charitable participation in one domain and expansion in another poses a model of displacement. In this model, the decline in participation in giving to and volunteering with nonprofit organizations is caused by a countervailing increase in giving to and volunteering through unregistered entities, or direct giving to individuals, or other expressions of generosity outside the bounds of the nonprofit sector. But other causal arguments can be advanced as well, in part depending on whether there has in fact been a shift in practice, and not merely in public attention, toward informal and unregistered giving and volunteering. It is possible, for instance, that the causation runs in the other direction, with the decline in giving to nonprofits sparking compensatory interest in other expressions of generosity. Some have inverted the causal relationship entirely, arguing that it was the hyper-fixation on monetary gifts, and especially those from wealthy donors, that precipitated the decline in everyday donors—and that the current attention being directed to such donors, as well as to informal expressions of generosity, represents a necessary corrective.11

In any case, the increased focus on informal expressions of generosity has introduced a measure of indeterminacy into the study of generosity, since many of these less formalized ways of giving resist or complicate efforts to quantify, measure, or track them. Additionally, the growing popularity of private, online platforms on which an increasing amount of giving now takes place means that much of the related data is in the hands of for-profit corporations with no legal or regulatory requirement to report aggregate giving data. Finally, the spread of many of the new instruments of generosity has helped to erode the clear conceptual and legal boundaries that had facilitated tracking (and often legitimized financial support) of gifts to nonprofit organizations. As scholar Lucy Bernholz has written, “Online giving has … helped blur the lines between giving to nonprofits, for-profits, individuals, or politics as each of these options looks basically the same on a crowdfunding platform.”12

In the last few years, more researchers have sought to meet the challenge posed by these informal modes of generosity and to track and collect data on their growth and development; this chapter relies heavily on the fruits of those labors. Yet at the same time, surveying the more expansive generosity ecosystem will require becoming more comfortable in an uncertain terrain and embracing some elements of provisionality and imprecision in our understanding of giving and volunteering trends. This does not make the investigation any less urgent or its results any less consequential, but it does mean that findings will likely look significantly different from those that have come before.

The following landscape analysis of the generosity ecosystem summarizes what we currently know about the decline in giving and volunteering rates, with a particular focus on the “dollars up, donors down” (or “volunteer hours up, number of volunteers down”) dynamic and how it was manifested during the COVID-19 pandemic. The landscape analysis assesses the evidence base for this dynamic and examines why it is of concern to many within the charitable sector. It then outlines some of the most frequently cited explanations for the decline of donors and volunteers, including economic precarity and experience of the Great Recession especially, declining religiosity and institutional affiliation, reduced tax incentives for giving, declines in the public’s trust of institutions, increased social disconnection, and demographic shifts and generational succession. The final section of the analysis reviews the evidence behind another potential explanation: that giving to nonprofits has been displaced by other forms of giving and prosocial behavior, such as crowdfunding, person-to-person giving, community care, and political activism. The analysis finds that there is, as of now, no clear evidence of displacement beyond anecdotal accounts, and that more data is needed—especially longitudinal data—to arrive at any definitive conclusion about the relationship between various forms of giving and volunteering participation.

Declining Donors